"We were landlocked, lifelocked, mindlocked..."

The following is a dialogue between Norwegian activist Kristin Eskeland and myself, published as a chapter in her book "The Young Voices of the World", also covering activism of young Albanians in 90s

This is a chapter in a book that starts with a comment by the author Kristin Eskeland, a former teacher, a Quaker and a children’s’ rights activist. She has worked in former Yugoslavia, Middle East, South Africa since 1980s and was instrumental in getting Norwegian government involved in supporting projects in Kosovo at the time when no one really cared too much about Kosovo. The chapter covers creation of a youth NGO Postpessimists in Kosovo, which was co-founded in 1993 by a bunch of kids - and friends - such as Jehona Gjurgjeala, Yll and Ylber Bajraktari, Jeta Xharra, Garentina Kraja, Fisnik Abrashi, Nita and Zana Luci, my brother Dren, Ariana Morina, Nita Salihu, myself - and hundreds of others.

“We were landlocked, lifelocked, mindlocked in Kosovo. Completely locked out of everything by the new regime of Milosevic. Back in 1991, he put an end to Kosovo’s autonomy and started the vicious wars in Croatia and Bosnia which raged for several years.” - Petrit Selimi

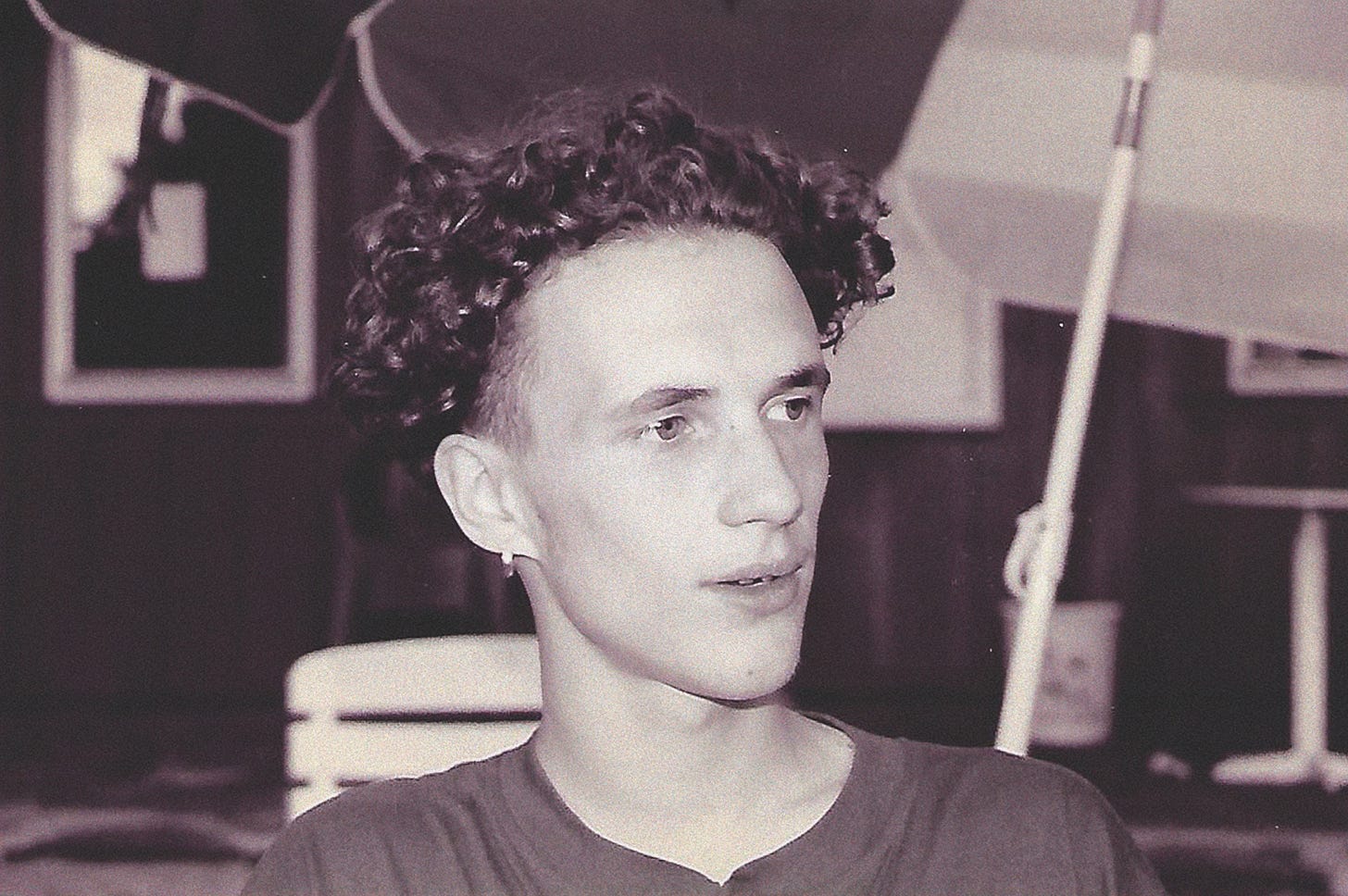

KRISTIN ESKELAND: Petrit was only 14 in 1993, but he was the one who more than anyone got the ball rolling. He was always full of ideas and projects. Without him the PostPessimist movement might have ended up with just a meeting or two. In order to understand the background of the PostPessimists it might be useful to tell the story of Petrit’s background and his upbringing. Not because it was so different; on the contrary, simply because so many of the young people who became PostPessimists in Kosovo had similar backgrounds.

One may think Petrit being in many ways born with a “silver spoon in his mouth,” as we say in Norway. Yet, this is far from truth. Because of the situation in Milosevic’s Yugoslavia his youth—a shared experience with all other kids in Kosovo— became quite different from what their families had imagined. His story might make it easier to understand what happened and how these young people reacted. (Kosovo-Albanians today call their country Kosova; in English it is called Kosovo).

Postpessimists became a center for providing young people with skills which they used well later in life. Decades later, Jeta became award-winning TV anchor, Jehona founded a youth NGO, Yll and his brother Ylber started working in Washington DC in the innovative field of Artificial Intelligence, Nita is now Kosovo’s Ambassador in Norway, Tina worked for first woman President of Kosovo while Fisnik and Beni are senior editors for Associated Press. The younger Nita is graphic designer, Dren opened a private baking business, Zana is a doctor, Ariana is an architect…

Petrit became foreign minister of his own country.

Here’s Petrit’s story.

PETRIT SELIMI: Things fall apart. 1992 was a strange year for us in Kosovo. A strange wave of unwarranted optimism was in the air, despite the very difficult political situation. The Berlin Wall had just been torn down and the expectations were that the European Community might become the United Europe. All over Kosovo new restaurants and bars turned up with names like “Europe 92.” Young people walked around singing “Unite—Unite Europe,” the name of the song sang by the winner of the European Song Contest that year. Everything was supposed to get better. Yet, nothing was.

I was thirteen. Born and raised in Prishtina, the drab capital of Kosovo. Until then, I had lived in Kosovo, which was then part of a country called Yugoslavia. It was a communist country with a leader called Tito.

I was born one year before Tito died, but growing up, his picture was in all our school books. Schools had both Albanian and Serb pupils and we learned that we must live in “Brotherhood and Unity.” Tito had apparently said that we must “protect brotherhood like the apple of our eye.”

But behind the scene, the rule was dictatorial. Kosovan Albanians were targeted for their “irredentist” activity and activists like writer Adem Demaçi were serving decades-long prison sentences for speaking the truth of oppression.

My mum’s name is Violeta; she was a “book doctor.” She had studied chemistry of book pathologies in Rome and specialized in restoring old books, mostly Korans and Bibles found in forgotten corners of old Ottoman houses. She used to work in the National Library of Kosovo and I could visit her there, lending comic books and hiding under her desk to read the latest adventures of Donald and Mickey and other series. In the mid 80s the library got its first computer and occasionally I was allowed to try it. I was in heaven playing the first ever version of Tetris.

My dad’s name was Selajdin, but he was known as Selush. He was a constitutional lawyer and worked as the Secretary of the “Constitutional Court of Autonomous and Socialist Province of Kosovo.” According to the changes to the Yugoslav Constitution of 1974, Kosovo had very wide autonomy and had its own parliament, government, university and police force. Kosovo had an equal legal vote and veto in the Yugoslav Presidency.

Before 1974 Kosovo was more or less under Serbian direct rule, harassed by the brutal secret police. After 1974, the conditions softened a bit, but Yugoslavia was no democracy. The secret police were still everywhere and life was not easy for most of the people in Kosovo.

In the 1980s I did not know so much about all this; as children we were shielded from the grown ups’ worries. I remember whispers and the worried looks, but apart from that I had a relatively happy childhood, as kids tend to have even in most miserly circumstances. In school we learned that we, the Albanians, were the descendants of the Illyrians, and that “we were here first.” First the Illyrians, then the Romans, then came Slavs and then the Ottomans. And finally Yugoslavia happened with forced “brotherhood and unity.” Linear version of history, with black and white characters.

Before 1974 boys in Kosovo were mostly named Mustafa or Muhammed (or Selajdin); after 1974 kids were given Albanian names like: Dren (Stag), Hana (Moon), or Arta (Golden). My own name means “hawk”. Or maybe “falcon” (I never know the difference). It was a sign of a new-found attention for our language and identity.

In August of every year we used to travel to Greece in our Citroën Visa. We brought with us all the food we needed in a small fridge in the back of the car. Dren, my younger brother, and I had plenty of time to play and romp around. Safety belts and children’s seats were unheard of. Both my parents were heavy smokers and we had plenty of stops on the way to get some much-needed fresh air.

But towards the end of the 80s things began to change in our little universe. Wheels began to turn rapidly until they started falling off. Our parents looked worried and whispered even more to each other. The entire world was about to change forever. It started with demonstrations and protests in the streets.

We lived in the centre of Prishtina, and our flat was always full of guests. My mother was a good cook; relatives came in from the villages, and Dad’s friends would come to play cards, smoke or just talk politics. There was always a lot of life at the Selimis. We grew up with many guests, all the time. Living in the city centre also meant that when the protests started, all the violence, blood, and tear gas, unfolded in front of our eyes. We became aware of what was happening around us.

Up the street first came the coal miners, then the students, then everyone. Police and tear gas everywhere. We learned to make homemade gas masks out of plastic yogurt cups and wet cloth; we thought we looked pretty cool. But of course the masks did not protect us from anything, and the windows in our ground floor flat let through quite a lot of tear gas. Goleshi street, where we lived, was the main street for the protestors who marched in central Tsar Lazar Square (Serbs had changed the name from Tito Square. After liberation, this is now “Mother Teresa Square”). Back in late 1980’s and early 1990s, on the way up, carrying banners and flags and pictures of Tito and local Kosovan leaders, on the way down they were usually running in terror, often bloody with police at their heels. After a while, Tito’s phoos were gone. That naive idealism of some was gone too. Yugoslavia became too violent. Too hateful towards Albanians.

If the protests lasted into the night, our parents would tell us it was “fire crackers,” as they did not want to scare us. They were, however, real shots. People were hit and we might see wounded people in our street in the early hours of the morning. This was the beginning of the last decade of the 20th century.

Maybe I need to tell you a bit about my family; it belongs in the story. Our family was very “political.” Even though our parents tried to shield us from their worries, we grew up with a lot of politics around us, at the breakfast table, at lunch and at supper. Our grandparents were larger than life. On my father’s side there were Babush and Nona or Xhavit and Nazlije; they lived in Presheva valley in southern Serbia. This was an Albanian-populated area just east of the Kosovo border, inside Serbian territory.

Nowadays most of the original inhabitants have moved, either to Kosovo or to Switzerland. My father was one of four children. He went to a Serbian school because Albanian schools were not allowed. They moved to Prishtina in the 1960s. He helped us kids with homework when it came to essays and languages; our mother helped us with math and science.

My aunt Nifa was my favourite, she made the most wonderful garlic and yogurt pies called samcë. When I later moved to Norway as a sixteen year old, alone and scared about the future, I dreamed of her and her pies when I felt alone in the dark Norwegian nights.

My other aunt Qamile (Mila) was a journalist who had studied in the USA as a youngster and was very updated and very smart. Her husband Veli was a caricaturist and I loved visiting them because they always had lot of books with caricatures.

My uncle Vasfi was very close to my dad. They played cards together (gin or “zhol” usually), debated politics together, we frequently went to holidays together. Uncle Vasfi took ages to reply to whatever hurried questions we had as kids. He still speaks like that on the phone. I always think telephone is broken waiting for his answers.

My motherˇs parents were Baba and Mama, or Asllan and Nurije. Asllan Fazlija was not the regular Joe Sixpack. He was nominally a socialist, but everyone knew that he was first and foremost an idealist and a true patriot. I was told from early childhood that I resembled him.

My grandfather was publisher in Rilindja publishing house, but also a former provincial official, having served as a minister both in the federal and in the local parliament, yet he was also attacked by Serb communists for harboring “irredentist” sentiments. When he died his coffin was placed in the central hall of Kosovoˇs parliament and there was a queue across the main boulevard to see the coffin and say goodbye. The wake lasted for 40 days and thousands of people came to express their condolences. He may have been first Albanian to receive Légion d'honneur medal by a French president.

In the midst of all this was Nurije, my maternal grandmother. The word stoic would suit her best. Her father was the head imam of the central mosque; as a small girl she was supposed to wear a hijab, but she refused. Her father tried to punish her and would not let her leave the house. But after six weeks he had to give up. She was a stubborn little girl, and she became a stubborn lady. She considered herself an equal to all men. The truth is probably that she was superior to most, both in will and in wit.

Then came the summer of 1991. As usual we were on vacation in Greece, but suddenly we had to return home as my other grandpa Xhavit had died of heart attack. As it happened, in the course of the next few weeks Serbia also (re)occupied Kosovo. Like all other state employees my parents were fired from their jobs, just because they were Kosovo-Albanians. We would never go to Greece again. Our childhood was over.

Things really fell apart in 1991. And 1992 was not to become the promised year of a United Europe like the song of Toto Cotugno had promised.

Darkness engulfed our world. All of a sudden we were not “middle class” anymore—people with an average income doing average things like going to Greece in the summer and buying Playmobile toys for their kids. We all became actually very poor. (Un)fortunately we were not alone; all of us were poor all of a sudden. Or almost everyone. Those who had the nerve and were street-smart could trade on the black market and the like—they managed. My parents were totally unfit for that sort of thing. They were completely unprepared for this dramatic change in their lives. They had no savings, no idea of what to do without their safe jobs. Smuggling was completely out of their league.

So here I was, in 8th grade of primary school, when the Serbs closed our school. It used to be an ethnically mixed school, but since it was situated in the center of the city the new government wanted the building for themselves. They simply kicked us out, the Albanian kids, in a matter of a few minutes. I remember the scene vividly: first of September, first day of school: I was 12, my brother Dren was 8. We were in the school yard, waiting to be allowed in when Serbian cops in black riot uniforms told us we had five minutes to get lost. We ran. I could say we ran like Forest Gump, but this was more chaotic and sinister. There was no good soundtrack accompanying our running.

Albanians opened their private houses and a sort of parallel school system was created in people’s basements or living rooms, as . To tell the truth, there was not much learning going on in those houses. It was a show of resistance, not a pursuit of academic excellence. My mother taught us English at home.

About this time in 1992 my mother received a telephone call from a friend of hers; a call which would change my life. An Englishman, David Woollcombe, was coming to Prishtina, and he wanted to get in touch with kids who spoke good English. He wanted them to participate in a theatre play. An odd proposal, but exciting! There were few foreigners in Prishtina in those days, and I had never met an Englishman, other than as tourists in Greece. We were landlocked, lifelocked, mindlocked in Kosovo. Completely locked out of everything by the new regime of President Milosevic. He occupied Kosovo and started the vicious wars in Croatia and Bosnia which were raging by 1991. A genocide in Kosovo was also being prepared. What remained of former Yugoslavia was put under UN sanctions for instigating wars in the Balkans, and we were completely under the Serbian heel.

So when David came to Prishtina we were full of stories about our new lives, protests and killings, ethnically segregated schools, fears of a looming war… David asked a lot of questions about our hopes, dreams and experiences. We were about ten kids; I was probably the youngest at 12.

David left the city, and that was it. But months later there was a new phone call, this time from England. Three of us, Pasionarja, Lyra, and I, were invited to come to a youth conference in Austria. This sounded like a fairy tale—fantastic, completely amazing. I had never been to Austria, never been out of the country since our world collapsed that horrible summer of 1991. The conference would take place in a small mountain village called Mürzsteg, a municipality in Mürzzusclag. A chance not to be missed!

Travelling to the conference was difficult. Serbia was under sanctions so there were no flights. We were driven to the Hungarian border by Lyra’s parents and my dad, in a very old Mercedes car owned by a cousin of ours, uncle Elez. We were to meet a Hungarian called Miklos Banhidi who would help us get to Austria. So we departed and somehow arrived in this little village in Austria. It felt like carnival time!

We were practicing for a children’s play dedicated to peace, together with kids from all over the world, many from similar conflict zones. I met a Serbian boy, Ivan, and a Croatian girl, Danijela. Serbia was the enemy, but we had no problems talking to each other. Regular Serbs were also impacted by Milosevic’s rule. He was killing Serbian dissidents too. We had workshops and practiced for the play. We walked around singing over and over: “Warum, warum gibt es Krieg?” I met Kristin Eskeland, a Norwegian quaker lady who ran some of the workshops. She was working for Norwegian People’s Aid. She made us feel safe and somehow at home.

And then we went on to Vienna, just to discover that there were even greater events waiting for us. A UN Conference about Human Rights, Dalai Lama was there, and all kinds of exciting things. We brought with us a HUGE real tree, which we had decorated with all our wishes and demands for a more peaceful world. We made a newsletter with our Peace Tree on the front page. It was printed in the Austrian paper the Daily Standard and we felt like rock stars. All this gave us a taste for more activism. We felt our voices must be heard, while madness was going on.

I had an idea, so I asked Kristin: Couldnˇt we organise a youth conference like this, but only for us, the war-torn Balkans? A mini-UN conference only for young people from Former Yugoslavia, just to get to know each other. I was from Kosovo, Ivan from Serbia and Danijela from Croatia, young people who seemed stuck in a series of wars just a few hours away from Vienna. Kristin understood. This is the thing about Norwegians. They will always support kids proposing projects to reconcile and fight for a better world.

Lo and behold: A few months later, Ivan, Danijela and I were writing a proposal to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, to organise an event for kids from Former Yugoslavia, and help maintain some links across the war trenches! For me it was clear from day one that young people from Kosovo needed the opportunity to get out for a week away from the darkness at home and experience the same feeling of empowerment that I had, while at the conference in Vienna. This would be our little contribution to the big movement of resistance.

Independence! Freedom! You may think that these are big words, that a bunch of teenagers could not possibly think in these terms, but we were dead serious.

And we had Kristin backing us up. It felt like having Wonder Woman on your side fighting the evil guys. I went back to Prishtina. While in Vienna, I had used all my savings for that and the pocket money for the following year on a joy stick to play video games with my Commodore 64 computer. But I was even more excited over the idea of doing something bigger than ourselves.

We started organizing ourselves into a small movement of children and youth focused on bringing to the rest of the children in our high schools in Prishtina the journalism skills, cultural activity, theatre plays, music concerts, publications, all focused on human rights activism and resistance – so our voices could be heard.

KRISTIN ESKELAND: Petrit continued being an active participant in the PostPessimist activities until the network died down around 2006. He participated in all the meetings, he played an active part in Dado’s theatre plays, he took part in all the discussions, never stopped talking and quarrelling about political questions, as he was always fiercely advocating for an independent Kosovo. Kosovo’s situation was always at the centre of his thinking and arguing. A born politician! He had the opportunity to take his “A-levels” at a Norwegian school in Oslo and he studied at Oslo University. He could have stayed in Norway where he could have an easier, more peaceful life, but chose to return to Prishtina. His family’s flat in the centre of the city where he grew up was turned into the “Strip Depot Cafe” after the war of 1998-99. A place where anyone could come and have a cup of coffee, read the comic strips and discuss politics. For years The Strip Depot was a meeting place for international journalists of all kinds. Petrit was a never-ending source of information and contacts. Together with journalist friends, he founded a newspaper and they named it Express, which focused on bringing new type of investigative journalism in Kosovo. At the age of only 25 he was the publisher of the paper, with responsibility for 70 employees. When Kosovo declared itself an independent republic in 2008, Petrit sold his shares in Express, and became an actual politician. He was appointed Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs and later became the foreign minister throughout Kosovo’s first period as an independent country.

His love of digital communications followed him in his role as a politician. He initiated an intense effort through Facebook and other social media in order to make Kosovo known and recognized by as many nations as possible. As a minister he was fighting for his country through digital diplomacy; he was behind a series of international conferences as a contribution to regional cooperation and interfaith dialogue. In 2012 the Kosovo Foreign Ministry organised a three days conference for young people from the Balkans, giving them the opportunity to exchange experiences and develop creative methods to solve common problems. At the next election Petrit’s party lost their majority, but prior to this, he had chosen to do something else for a while. He led Kosovan efforts to obtain development funds from US government, and Petrit is now the Director of the Millennium Foundation Kosovo, administering a 49 million dollar investment in clean energy and good governance from the US, thereby continuing some of the same work that he was engaged in as a child leader of PostPessimist movement.

He lives in Prishtina with his wife Arlinda and his son, Rrok Trim.